Improving or Maintaining Mental Health

Clinical Basis

Multiple factors impact this important and heavily weighted measure, which is captured from the HOS. Changes are measured over a two-year period.

Mental health issues can be experienced across the life course, and can co-occur or have a bidirectional relationship with other chronic conditions or disease. The mental health of older adults is often overlooked, considered simply to be a natural consequence of ordinary age-related decline of psychological and physiological health. Poor mental health is not a natural consequence of aging and is treatable.

In older adults, poor mental health is associated with lower quality of life, lessened ability to handle social functioning, and lowered pain tolerance (Jun & Aguila, 2021). Sixty percent of older adults with depression also suffer from anxiety (Hall et al., 2016).

The rate of suicide in males is highest for those aged 75 and over (40 per 100,000) (Hedegaard & Warner, 2021). Of patients with a primary health care contact prior to suicide, patients over 50 years of age had significantly higher primary health care contact rates both at 12 months (80%) and one month (44%) prior to suicide (Stene-Larsen & Reneflot, 2019). Demonstrating the important preventative role primary care plays for the mental health of older adults, as the site where mental health screening, follow-up and access to quality treatment can be facilitated.

Many older adults with depression however, often fail to receive appropriate and effective treatment due to fragmented service delivery systems (SAMHSA, 2011), stigma and cost of care. It is well demonstrated that patient outcomes improve when there is collaboration between a primary care provider, case manager and a mental health specialist to screen for depression, monitor symptoms, provide treatment and refer to specialty care as needed (SAMHSA, 2011) and that these are most effective when delivered in a framework of recovery. Models such as the IMPACT Collaborative Care Model for example has been highly effective for managing late-life depression (Unutzer, et al., 2002) and lends itself to replication.

Clinical Guidelines

- The USPSTF recommends that screening be done with adequate systems in place to ensure accurate diagnosis, effective treatment and appropriate follow-up.

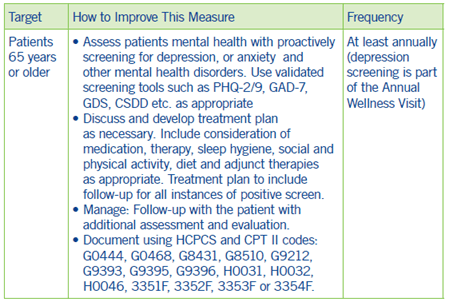

Coding and Documentation Guidance

Depression and major depression are diseases that require extra time to document appropriately.

- If patients have depression or major depressive disorders, it is imperative that physicians document the patients’ current signs, symptoms and treatment.

- In addition, it should be noted if this is the patients’ first episode of depression or if it is a subsequent/recurrent episode.

- The patients’ response (or lack thereof) to treatment must also be documented.

- A single incidence of major depressive disorder is coded “F32.9 Major depressive disorder, single episode, unspecified.”

If your documentation indicates that the patients’ major depression is ongoing, coding from the “F33 Major depressive disorder, recurrent section” may be appropriate.1

1 See Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5 at https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787